Secrets of the Oak Woodlands: Plants and Animals among California’s Oaks

by Kate Marianchild

Chapter Excerpts

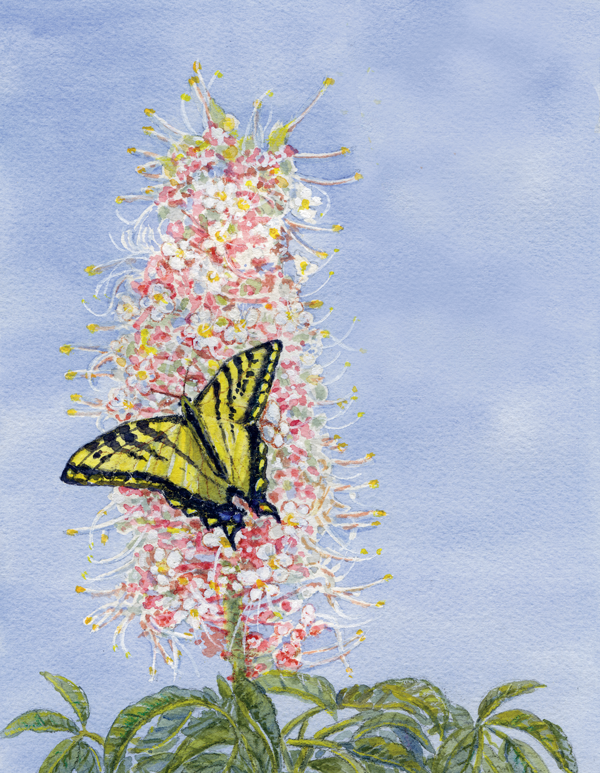

Excerpts from the California buckeye chapter

“California buckeyes unfurl their soft, many-fingered leaves in late winter and early spring, bringing luminous green cheer to landscapes still clad in somber grays. In May and June they again brighten our hillsides and canyons by transforming into giant flower candelabras, and in fall their seeds—the largest produced by any California native plant—droop like exotic testicular ornaments from bare silvery branches. The seed husks later crack open, allowing glossy brown “bucks’ eyes” to peek out between thick greenish lids. In winter, sculptural trunks adorned with moss and colorful lichens curve skyward while festoons of light green lace lichen dangle from the trees’ upper reaches.” (p. 21)

“By producing large, five- to seven-fingered leaves as early as February, buckeyes get a head start on the growing season, gathering sunlight before the rainy season ends and before other trees leaf out and engulf them in shade. While other trees are still dreaming of spring, buckeyes’ leaves are already in high gear, photosynthesizing the sugars necessary for the growth of trunks, branches, flowers, seeds, and leaf buds. In a stroke of evolutionary genius, the leaves of this “summer deciduous” species start turning yellow when the trees begin to go dormant, often as early as July, sidestepping the problem of water loss during the driest months. When water is plentiful they keep their leaves into fall.” (p. 22)

“If you have a chance to look at buckeye flowers with close-focusing binoculars, you will enter a microcosmic world impossible to imagine from what you can see with the naked eye. In addition to close-up views of butterflies, you will see highly magnified beetles, flies, and native bees, all with their own interesting shapes and sheens, quietly gathering nectar/or and pollen. Because they have coevolved with the California buckeye for countless millennia, native insects have acquired resistance to its toxins.” (p. 23)

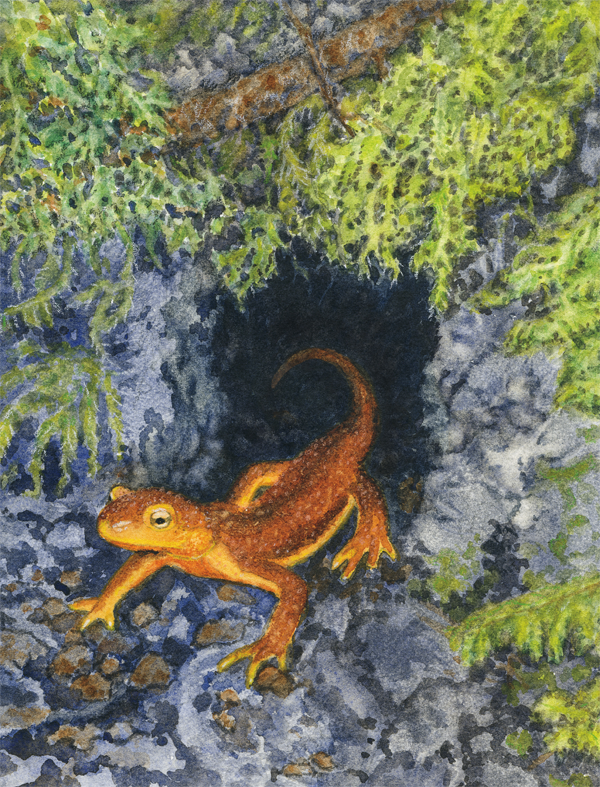

Excerpts from the California newt chapter

Three dead hunters–– “In the predawn coolness of a fall day around 1950, a hunter in a campsite somewhere in Oregon’s Coast Range walked to a stream with an empty coffeepot. After scooping up water in the darkness and walking back to camp, he set the pot on the grill, added coffee grounds, and boiled the coffee. As the sky slowly lightened, he poured three cups, handed one to each of his two companions, and saved the third for himself. While sipping their coffee, the men began to notice tingling in their lips and hands. Soon they were vomiting, and within thirty minutes all three hunters were dead. When hikers found them two days later, there was no sign of foul play. The only unusual thing in the campsite was a dead rough-skinned newt in the coffeepot.

Curious about whether the newt in the coffeepot could have caused the deaths, a young biologist named Edmund Brodie Jr. began observing rough-skinned newts in the early 1960s. When he saw frightened newts raising their heads and tails to show off their bright undersides, he got serious. In the animal world, eye-catching, or “aposematic,” coloration often means “I’m toxic––eat me at your own risk!” (p. 49″

“Shaped roughly like lizards, but no more closely related to them than to mammals, California’s newts appear magically after fall, winter, and spring rains, plodding purposefully across roads, trails, meadows, and leaf-littered slopes. Their painfully slow progress suggests suicidal tendencies, but they have little to fear from most predators as they are protected by whopping amounts of a potent poison. They make epic journeys with an unerring sense of direction and, like most amphibians, have the ability to “breathe” in water as well as air. But their most amazing talent may be the ability to regrow perfect organs and limbs.” (p. 45)

Excerpts from the California quail chapter

“Whrrrr! In the dimming shadows of dusk a covey of California quail explodes into flight, foiling the dinner plan of a stalking bobcat. The thirty-odd birds fly a dozen feet and land on the low branches of a live oak, murmuring to each other until the cat has wandered off.

With heavy bodies and strong legs, quail are designed more for life on the ground than for flight. They rarely fly farther than the nearest tree or shrub when escaping from danger. Hunted for millions of years by hawks, snakes, and mammals—including humans for the last twelve to fourteen thousand years—these birds are extremely skittish.” (p. 55)

“Soon after they hatch, quail chicks have to follow their “ut-utting” parents out in the world. Before they hatch, therefore, they must imprint on the sound of their parents’ voices. To this end, quail parents talk to their eggs. Embryos that are almost ready to hatch also talk to the other embryos from inside their eggs. They click, peep, and chirp as if to say, “I’ll be ready to come out in about fifteen minutes; how about you?” They have the amazing ability to speed up or retard their hatching process based on the information they receive back. For the embryos to communicate, the eggs have to be touching each other.” (p. 58)

“Quail were a favorite food of the Pomo peoples, who, along with the Miwok, Maidu, Patwin, and other tribes, developed quail snaring and trapping to a high art form. It was common for hunters to build special fences with regularly spaced gaps fitted with nooses or long narrow cylindrical baskets. Hunters were known to build half-mile-long fences that, in spring when the birds were migrating to higher elevations, could catch fifty quail in one day.

Open at both ends, the basket traps tapered gradually from one end to the other so they could be fitted together to make long tubes. The final basket in the series was closed at the narrow end. A trail of food would lead a bird into the first basket, and all the other birds would follow until they reached the end, where they were unable to go forward and unable to turn around. Pomo inventors also applied their considerable engineering skills to the design of ingenious treadle snares and box snares. In addition to valuing quail meat, Pomo peoples also treasured quail head plumes with which they decorated exquisite baskets and clothing.” (p. 60)

Excerpts from the California sister chapter

“The first time I see a California sister butterfly flutter by each spring, my heart flutters a bit too. These are the most colorful of our early spring “flying flowers” and their appearance reassures me that life in the oak woodlands is gliding along much as it has for millennia. It means female butterflies laid their eggs late the previous summer or fall, caterpillars hatched and ate oak leaves, and just before winter the caterpillars built nests to protect themselves from the cold.

It is no coincidence that California sister and its two North American cousins have the eye-catching colors, regal flight patterns, and earthy diets of tropical butterflies… (p. 65)

“Sisters lay green eggs singly on the upper edges of the leaves of mature, usually evergreen, oaks—most frequently coast live, interior live, and canyon oaks. The larva (caterpillar) that hatches from one of these eggs is camouflaged in speckled oak-leaf green. As it feeds and grows, the larva sheds its skin four times over a period of weeks. Each new “instar” (larval stage) looks different from the previous one. The fifth and last is perfectly camouflaged with a green body and six pairs of yellowish “horns” that echo the spiny points characteristic of many live oak leaves. (p. 66)

Ecology Reference Guides (ERG’s) are found at the end of most chapters. They contain information on web of life relationships, diet, reproduction, predation, life span, seasonal cycles, migration, etc. Below are two of the eight sections that comprise the ERG at the end of the California sister chapter. Similar Ecology Reference Guides are found at the end of most chapters.

Food Requirements

“Adults eat dung, carrion, flowing sap, rotting fruit, fruit pecked open by birds, and aphid honeydew; nectar from California buckeye, toyon, yerba santa, dogbane, giant hyssop, goldenrod, and coyote bush; also minerals and amino acids from moist mud. Larvae eat the green leaves of oaks, especially canyon and other live oaks.”

Reproduction and migration

“One to three generations of adults emerge and fly per year, beginning in March or April and ending in November at lower elevations. They lay eggs singly on tips of oak leaves, on the upper surfaces. There are five larval instars. Partially grown larvae overwinter. In early spring they complete their larval stages and pupate. Females migrate far and wide in fall for unknown reasons.” (pp. 68-69)

Excerpts from the coyote chapter

“The first time I slept in my yurt, a cacophony of yips and howls sliced the night, sailing through my open window from a point about twenty stone’s throws away. Twelve years later I still get goose bumps when I hear coyotes. Their crooning carries me back along moonlit trails toward a primal wildness I long to rejoin. I want to sit skin-to-fur with the “song dogs,” muzzle raised, howling to their eerie harmonies.

Coyotes are keystone carnivores who keep their local ecosystems healthy by controlling populations of small plant-eating and nest-raiding mammals. They also strengthen populations of deer and other ungulates by culling genetically weak individuals from the gene pool. These intelligent and resilient animals have managed to expand their range across North America in the face of more than a century of extermination campaigns by humans.” (pp. 71-72)

“If you stake out a ground squirrel colony, especially at dawn or dusk, you might be lucky enough to observe the legendary relationship between Coyote and Badger. These two species appear to be hunting partners, often trekking in tandem toward ground squirrel colonies, where they scan the turf together for likely meals. While badgers rummage below ground for ground squirrels, coyotes nab the ones that burst out of burrows, catching about 30 percent more ground squirrels than they would if hunting alone. Coyotes get the better end of the deal, but they do help badgers by guiding them to fresh ground squirrel sign.” (pp. 73-74)

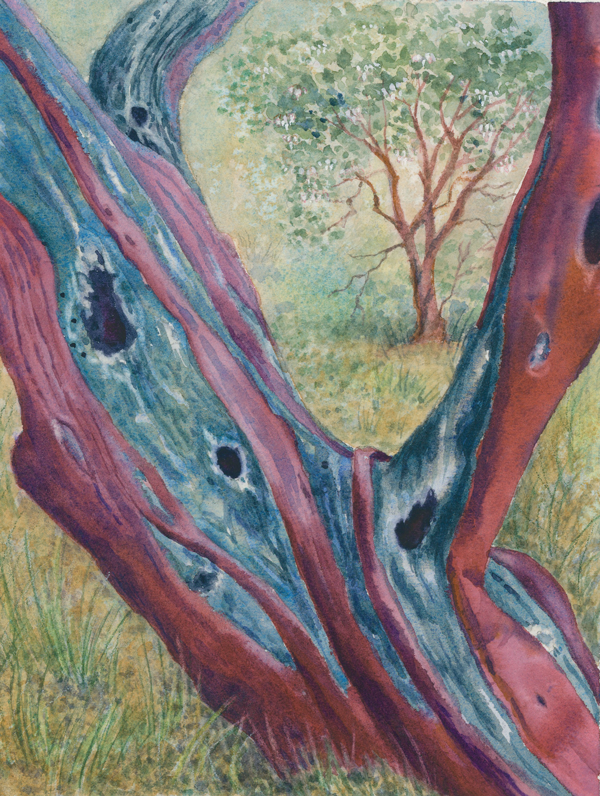

Excerpts from the manzanita chapter

“Manzanita first appears in the fossil record about 37 million years ago in central California. About 1.5 million years ago it began diversifying and dispersing to places throughout the West and as far away as Guatemala and Eurasia. Not surprisingly, the central California coast is the world hub of manzanita diversity. With an extraordinary ability to adapt to unusual habitats, the sixty-two-odd Arctostaphylos species come in a bewildering array of shapes and sizes, from two-inch-high ground covers to tall shapely trees.” (pp. 85-86)

Excerpts from the western gray squirrel chapter

“When you see branches swaying high in the oak canopy on a windless fall day, prepare to watch heart-stopping acrobatics. A western gray squirrel may be bounding from branch to branch sixty or eighty feet overhead. These daring gymnasts sometimes leap across twenty-foot chasms to land on finger-sized twigs that careen wildly under their weight and occasionally break. Other times the graceful athletes seem to float through the treetops, shining tails undulating like waves behind them.” (p. 161)

“The tails of western gray squirrels serve at least eleven purposes, probably more. When one of these trapeze artists falls out of a tree (a rare but not unheard-of event), it uses its tail as a parachute. Then, just before hitting the ground, it flips its tail under its body to cushion the fall! When you see a squirrel crouching on a branch, tail curled over its body, it may be using the tail as a blanket, sunshade, umbrella, or camouflage device, depending on weather or the presence of an aerial predator. The tail camouflages the squirrel by reflecting light from every hair, making it difficult for a hawk or eagle to see the outline of its prey.” (pp. 165-166.)

Excerpts from the woodrat chapter

“Once upon an epoch, perhaps three million years ago, a storm-swollen stream tugged a log from a section of bank, leaving a mother woodrat and her newborns exposed and shivering with cold. With four babies clinging to her nipples, the mother scuttled away from the stream to the base of a boulder. Using her teeth, she pulled a few dead branches over herself and her infants, warming and hiding them. One baby eventually died of cold and two were eaten by rattlesnakes, but the one who survived imitated her mother and pulled a few sticks over her own babies when they were born a year later.

Scenarios such as this may have been enacted and reenacted multiple times over millennia before house construction “stuck” as a genetically encoded behavior of woodrats. Regardless of when or how it happened, it was a great day in prehistory when the first woodrat decided to build. Her descendants appear to create more elaborate above ground houses than any other mammal in the world besides humans. These structures serve their owners brilliantly and play a keystone role in oak (and other) ecosystems. The two species discussed in this chapter build the most magnificent mansions of all.” (pp. 183-184)

“A large, well-built woodrat castle is an architectural wonder––a multilevel complex of rooms, corridors, and terraces that might easily fill a space one thousand times the size of its single owner/occupant. Such a mansion can remain in use for over sixty years as generation after generation keeps adding foliage to the outside and remodeling the inside by chewing out new passageways and rooms. As you start noticing woodrat houses, you will be amazed at the architects’ ingenuity in using whatever building materials are locally available.

Large woodrat dwellings have three or four waterproof sleeping rooms that double as birthing nests and nurseries. Sleeping nests, which are often under logs or rocks in the safest part of the house, have been found to be dry after four days of drenching rain. Lodges also have pantries, leaching rooms, latrine areas, and openings that admit light and air to every level. The occupants line their sleeping nests with soft plant material such as thistledown or finely shredded bark and, clever fumigators that they are, they scatter leaves of California bay laurel around the edges when available. They nibble the outside edges of these leaves to release powerful volatile oils that kill seventy-three percent of flea larvae and other nest parasites. According to scientists, woodrats nibble bay leaves only for fumigation purposes––never for nutrition. A householder will replace used leaves with fresh ones every two to three days.” (pp. 187-188)

![]()